|

|

The Freshness Window

Understanding Perishable Sales

Submitted by Adam Smith, CFE, CFI

Senior Regional

Asset Protection Manager

Winn Dixie Stores

Each day companies around the world engage in the sale

of perishable goods, which are like a ticking clock that

counts down to a point when the product must be sold or

the product will be lost. The most common perishable

goods purchased by consumers are fresh foods sold by

grocers. Another common perishable good is live plants.

These goods have individual spoilage timelines; if not

met, will result in losses.

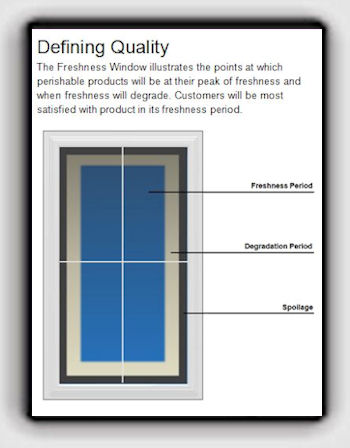

Perishable goods have a freshness period of a number of

days from harvest, which vary by specific item. In this

freshness period, the product is considered at its peak

quality regardless of the point within the freshness

period. After the freshness period ends, quality

degrades by each passing day. For example, a banana one

day beyond its freshness period is considered much

fresher than a banana four days beyond its freshness

period. During the degradation period, customers will be

increasingly dissatisfied with the quality of the

product. If too many days pass beyond the freshness

period, the product becomes spoiled. At the point of

spoilage, passing days are irrelevant. Fresh foods

illustrate this point best, but the concept is

applicable to perishable goods following the described

model.

The freshness period and the spoilage point vary by

product. As an example, fresh lettuce may have a

freshness period of 7 days and a spoilage point of 14

days. In days 8-13, the quality of the product will

slowly degrade to the point of spoilage. Ideally, this

product should be sold between days 1 and 7.

Alternatively, onions have a larger freshness period. The freshness period and the spoilage point vary by

product. As an example, fresh lettuce may have a

freshness period of 7 days and a spoilage point of 14

days. In days 8-13, the quality of the product will

slowly degrade to the point of spoilage. Ideally, this

product should be sold between days 1 and 7.

Alternatively, onions have a larger freshness period.

The period up to spoilage represents the Freshness

Window. The point when product is sold within the

Freshness Window represents the level of quality a

customer will experience. Providing products within the

freshness period is a way for retailers to add value to

perishable goods without increasing costs.

Alternatively, selling beyond the freshness period

reduces the value of perishable goods. Companies

providing goods within the freshness period will have

the highest customer satisfaction relating to quality.

Best-in-class operators will continuously evaluate and

discard products early in the Freshness Window. On the

other hand, struggling companies will be offering

products later in the Freshness Window, up to the point

of spoilage. Customers purchasing products late in the

Freshness Window will have a limited amount of time to

use the product before spoilage occurs. In many cases, a

good operator will throw product away at a point in the

Freshness Window that the poorly run operation would

still have available for sale. In this scenario,

customers of the poorly run retailer are eating the

equivalent of the competitor’s garbage.

Shrinkage Paradox

If freshness is such a huge opportunity, why do

companies leave product on the shelf outside of its

freshness period? The problem is rooted in the Shrinkage

Paradox. Shrinkage is the losses that occur from

discarding product. Some companies have intense pressure

to reduce losses resulting from shrinkage. This pressure

is frequently misinterpreted by line-level managers.

Often times, the line-level manager interprets reducing

shrink as keeping product available for sale longer. By

doing so, product is kept on the shelf past the

freshness period into degradation.

Every retailer of perishable goods has a tolerance of

the amount of shrink they will allow. Perishable grocers

typically allow anywhere from 5%-8% of total perishable

sales. As pressure to reduce shrinkage is increased,

most companies inadvertently expand their Freshness

Window to allow product more time on the shelf to

potentially be sold. This will reduce shrinkage slightly

to achieve desired levels. However, these efforts are

limited to the spoilage point of the product, because

the shelf life cannot be extended beyond it.

Opening the Freshness Window to reduce shrinkage will

only provide small and temporary reductions. By opening

the Freshness Window into degradation, customers will be

dissatisfied, and some will shop competitors. This

strategy will ultimately backfire due to the loss of

sales. The loss of sales will cause an increase in

shrinkage as a percentage to total sales. This is the

position of poorly run perishable operations.

Alternately, retailers with good operations will

continuously evaluate and throw out products that do not

meet their freshness standards. The quality of discarded

products from well run operations are much higher than

poorly run operations; however, these well run

operations will have shrinkage near poorly run

operations. Paradoxically, both operations will have

similar shrinkage figures, which ignore the quality of

product discarded. This will cause many to falsely

assume that both retailers have comparable operational

efficiencies.

The Root Cause

Shrinkage is normally higher in poorly run operations;

however, the real issue is the type of product

discarded. The true sign of a well run operation is the

freshness of the product available for sale. The

difference lies in how fresh the product being thrown

out it is, which is what compromises shrinkage. Good

retailers throw out product within the freshness period

before it begins to degrade. Fresher product increases

sales and customer satisfaction.

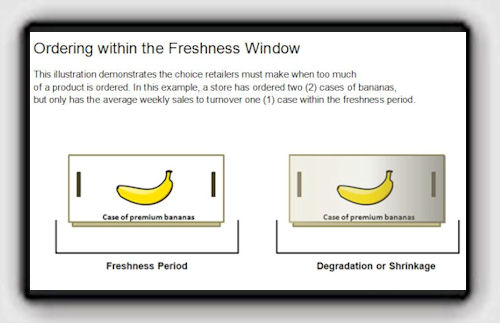

Selling product within its freshness period requires the

retailer to have sales to turn over the product within

said period. As sales increase, this becomes easier.

Assuming the freshness period for bananas is 7 days, a

retailer must average selling a case of bananas per week

in order to sell a case ordered within its freshness

period. Problems occur when a retailer orders more

perishable product than its average weekly sales

support. In this example; if the retailer sells one case

of bananas per week, ordering two cases will cause a

problem. At this point, a decision has to be made to

take a loss by throwing the product away or keep the

product available for sale past the freshness period.

Shrinkage is merely a symptom of poor ordering and

planning. The root cause of the issue is ordering too

much product. This notion is difficult to grasp for

some; precisely, because proper ordering is complex.

When selling perishable goods, the best information is

often in the form of projections. In the case of

industrial production, factories can place just-in-time

orders for a small group standardized parts. In a

grocery store, there are hundreds of perishable

products, which can come from different areas of the

world depending on the growing season. Each of these

products has a unique Freshness Window. This task can be

daunting; especially, considering the limited amount of

sales and inventory data available. Shrinkage is merely a symptom of poor ordering and

planning. The root cause of the issue is ordering too

much product. This notion is difficult to grasp for

some; precisely, because proper ordering is complex.

When selling perishable goods, the best information is

often in the form of projections. In the case of

industrial production, factories can place just-in-time

orders for a small group standardized parts. In a

grocery store, there are hundreds of perishable

products, which can come from different areas of the

world depending on the growing season. Each of these

products has a unique Freshness Window. This task can be

daunting; especially, considering the limited amount of

sales and inventory data available.

To a lesser extent, other procedures such as "cold

chain" can similarly reduce the freshness of perishable

products. Cold chain is a procedure to keep products at

required storing temperatures during transportation,

which can occur when a store receives product and when a

store moves product from storage into selling areas. If

perishable products are allowed to lose temperature

during this time, quality is reduced corresponding to

the amount of time without temperature control. Here

again, following these procedures serves to maintain the

quality of product that has already been purchased; not

doing so, decreases the value of the goods.

Quality Costs

Many retailers selling perishable goods choose to look

the other way as it relates to shrinkage, so long as the

number is within their tolerance. These companies are

falsely assured by their shrinkage figure being near the

industry average. However, as mentioned earlier, the

product thrown out (shrinkage) can vary in terms of

quality. The real issue concerns the quality of product

that is available for sale.

In a highly competitive industry, quality of goods is a

significant differentiator. Especially, considering that

improvements in quality can come at no additional cost

to the company. The goal is to maintain the freshness of

the product that has already been purchased, which is

accomplished by proper ordering. Ironically, few

retailers commit resources to improve this operational

area of their business. Perhaps, the Shrinkage Paradox

is masking their perception of the problem or the

organization does not truly understand the impact of the

problem.

Nevertheless, quality has a significant impact on

customer satisfaction. In a recent survey conducted by

the Food Marketing Institute in 2010, customers noted

product quality as the second leading consideration in

selecting a grocery store, which was only 2% less than

the leading consideration of price. In 2008, as part of

the same survey, customers identified product quality as

the leading selection criteria. As economic pressures

relax, retailers can expect product quality to take

center stage with customers.

Building a Structure

for Quality

Addressing the quality issue is not simple. Sales serve

as a feedback loop for product quality, so poorly run

operations will struggle most because of fewer sales.

Since products are sold by cases and packs, a retailer

needs enough sales to cover at least the smallest

quality available to be ordered within the freshness

window; anything else will be shrinkage. Increasing

quality will improve customer satisfaction, leading to

sales; however, there will be a lag period. In the

meantime, accepting the unsold product at the end of the

freshness period as shrinkage will be difficult.

Consumer demand for variety will add to this pressure,

because many niche varieties have low sales.

Complicating the ordering problem is the absence of good

sales data from these products. Some retailers stock

hundreds of different perishable goods, all of which

have a unique Freshness Window. Companies rarely have

item specific data regarding amount sold, ordered, and

discarded; if they do, the data is rarely uniform

between each measurement. This type of data is

instrumental in measuring each product’s Freshness

Window against the amount of inventory on hand.

Retailers need to know where their inventory levels

relate to the Freshness Window at all times. Reporting

on this metric will uncover ordering issues which may be

causing poor quality products to be sold. Understanding

which products have the largest freshness opportunity

will allow for strategic focusing on the problem.

Additionally, the retailer will be able to use this data

to measure the impact their Freshness Window is having

on sales, which may justify investments in training or

technology.

In some cases, a product may be identified as having

unavoidable shrink. Unavoidable shrink may be caused by

average sales within the freshness period that do not

cover the amount of product in a case or pack. Under

these circumstances, the retailer can choose to accept

the losses in order to provide variety for its

customers. If this option is chosen, the retailer should

keep track of all unavoidable shrinkage and include it

in budgets. In some cases, it may be possible to work

with suppliers to reduce case size to accommodate the

Freshness Window of the product. This would not be

possible without having the granular data to identify

these opportunities. As a last resort, a retailer may

choose to eliminate the product from its offerings.

By attacking the quality issue at its root, retailers

can improve the quality of perishable goods they have

available to their customers, without increasing costs.

An increase in quality will lead to an increase in

customer satisfaction, which will increase total sales.

Sales increases will allow the retailer to consider

stocking a larger variety of products that would not be

profitable at a lower sales volume. Retailers may need

to invest in new technology in order to capture the data

needed to develop successful freshness strategies. In

highly competitive industries, quality strategies are

critical to delivering exceptional value to customers. |

|

|

What's Happening?

Coming in 2012:

Keyword/Phrase Search

Research Capability

Mobile App's

LP Show Coverage

The Top 10

|

|